Canada’s statistics are not telling the complete story on construction industry deaths as the industry has come through a deadly 2022, and while figures record how fatalities occur, they tell little of the why or the trends in worker deaths.

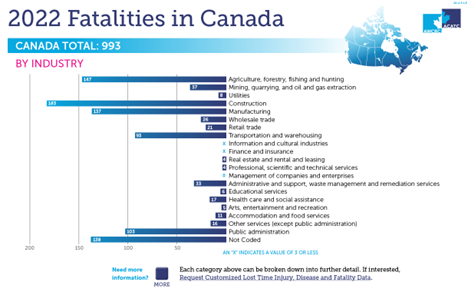

The construction industry figures from WorkSafeBC show 2022 saw 54 B.C. deaths, the highest in 35 years, and the Allied Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada’s figures show construction’s 183 fatalities outstripped other sectors.

BC Building Trades executive director Brynn Bourke said the figure of 28 trauma deaths surpassed the occupational deaths such as asbestos exposure, the past legacy of lax safety standards.

The trauma deaths “are a real warning,” she said, as there needs to be more inspections, more training, proper equipment and proper fitting personal protection equipment, especially for women.

Canada’s statistics are mainly gathered from workers’ compensation boards, a point that has drawn skepticism from two university reports as they indicate the figures are under-reported and not encompassing enough.

University of Ottawa criminologist Dr. Steven Bittle said: “We only report the claims that are accepted for compensation.”

Workers’ compensation boards were not established to record worker death or injuries in Canada, he said, but were established as an insurance system.

“The damage is much greater,” he said, as his research looking at comparative death and injuries statistics in the other countries concluded Canada’s rate could be as much as 10 times higher.

While Canada tracks asbestos-related workplace deaths, Bittle said there is no tracking of a wife who for years washed her husband’s asbestos contaminated clothing.

He has recommended governments take over the task of keeping track of workplace deaths.

A University of Alberta report also points out that workplace deaths or injuries don’t include workers killed in motor vehicle accidents travelling to work, private insurance, and provinces where a vehicle accident onsite can be claimed against the provincial system. The Alberta report, though, stresses statistics are important for establishing research on incidents.

In both Canada and the U.S., falls have been the leading cause of death in construction fatalities. However, the U.S. based Centre for ��������ion Research and Training (formerly known as the Centre for Protecting Workers’ Rights) has looked at the why and found senior individuals had a higher fall mortality rate.

“Older workers are also more likely to experience both hearing loss and diminished balance, contributing to falls,” the research body found.

The centre provides a section on aging workers with a recommendation of pairing younger physically-fit entrants with seniors who can impart knowledge.

Some factors are known.

“We do know that young workers can be disproportionately affected by injury,” Bourke said, adding there is a youth strategy in place.

The actuary figures have shown the B.C. construction industry is growing safer, said Dr. Dave Baspaly, president of the Council of ��������ion Associations.

From 1992 to 2023, WorkSafeBC premiums have dropped from $5.83 per $100 of assessable payroll to $1.61, an indication of a deepened safety culture on construction sites.

But the culture is also changing. There is an emergent focus on the human dynamics, risk taking and how a personal life impacts the jobsite, Baspaly said.

“We are starting to see what is in the realm of behavioral science, why people do what they do and what risks do they take and when.”

In Alberta, safety consultant Rick Peden, a 24-year industry veteran, has voiced concern over how socio-economic factors such as the federal government’s recent large influx of funding for housing will impact safety as there is a rush to build.

“There is pressure on the contractor or subcontractor to move onto the next job,” he said, causing incidents such as not putting on fall protection gear because it is only a 10-minute job.

In the U.S., foreign-born Hispanics and Latinos made up one in five construction deaths and Peden is voicing concern for Canada’s growing number of immigrants entering the building trades. They face language barriers and may not have an understanding of the safety culture, he said.

Or, they may derive from a culture where they were not encouraged to report safety hazards.

The New Brunswick ��������ion Safety Association’s CEO Roy Silliker said fatality statistics in Canada lag behind nationally, while provincial stats are more readily available. He would like to see more of a breakdown of statistics nationally for the construction industry, such as how long the individual worked in the sector.

He applauds the mental health programs appearing in the workplace as they can help identify factors relating to deaths, such as whether a fall was an accident or suicide, he said, a fact that a coroner’s inquest would bring forward.

“Coroner’s inquests can take up to two to three years to be heard and not all provinces hold inquests (on work-related accidents),” he said.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed